Sustainable Wealth

What is wealth? What is sustainable? How can wealth creation for our society be brought back into alignment with true happiness and well being? Where do wealth and sustainability intersect? Some say true wealth is "quality of life" - well then, What is quality of life? I'll survey thinkers, articles and topics to address these and related questions... "We don't see things as they are. We see them as we are." - Anais Nin

Friday, December 12, 2025

Sunday, February 23, 2025

A new dialogue with our human nature

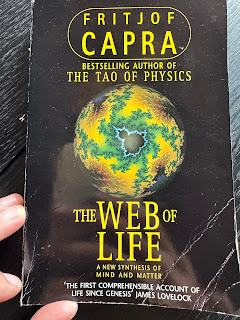

This passage Fritjof Capra’s 1997 feels book relevant to our time.

“ A NEW DIALOGUE WITH NATURE

The conceptual shift implied in Prigogine's theory involves several closely interrelated idcas. The description of dissipative structures that exist far from equilibrium requires a nonlinear mathematical formal-ism, capable of modelling multiple interlinked feedback loops. In living organisms, these are catalytic loops (i.c. nonlinear, irreversible chemical processes) which lead to instabilities through repeated self-amplifying feedback. When a dissipative structure reaches such a point of insta bility, called bifurcation point, an element of indeterminacy enters into the theory. At the bifurcation point the system's behaviour is inherently unpredictable. In particular, new structures of higher order and complexity may emerge spontaneously. Thus self-organization, the spontaneous emergence of order, results from the combined effects of non-equilibrium, irreversibility, feedback loops, and instability.

The radical nature of Prigogine's vision is apparent from the fact that these fundamental ideas were rarely addressed in traditional science and were often given negative connotations. This is evident in the very language used to express them. Nonequilibrium, nonlinearity, instability, indeterminacy, etc., are all negative formulations. Prigogine believes that the conceptual shift implied by his theory of dissipative structures is not only crucial for scientists to understand the nature of life but will also help us to integrate ourselves more fully into nature.

Many of the key characteristics of dissipative structures - the sensitivity to small changes in the environment, the relevance of previous history at critical points of choice, the uncertainty and unpredictability of the future - are revolutionary new concepts from the point of view of classical science, but are an integral part of human experience. Since dissipative structures are the basic structures of all living systems, including human beings, this should perhaps not come as a great surprise.

Instead of being a machine, nature at large turns out to be more like human nature - unpredictable, sensitive to the surrounding world, influenced by small fluctuations. Accordingly, the appropriate way of approaching nature to learn about her complexity and beauty is not through domination and control but through respect, cooperation, and dialogue. Indeed, Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers gave their popular book, Order out of Chaos, the subtitle 'Man's New Dialogue with Nature'

In the deterministic world of Newton, there is no history and no creativity. In the living world of dissipative structures, history plays an important role, the future is uncertain, and this uncertainty is at the heart of creativity. "Today, Prigogine reflects, "the world we see outside and the world we see within are converging. This convergence of two worlds is perhaps one of the important cultural events of our age.”

And the last page of the book:

“ In ecosystems, the role of diversity is closely connected with the system's network structure. A diverse ecosystem will also be resilient, because it contains many species with overlapping ecological functions that can partially replace one another. When a particular species is destroyed by a severe disturbance so that a link in the network is broken, a diverse community will be able to survive and reorganize itself, because other links in the network can at least partially fulfil the function of the destroyed species. In other words, the more complex the network is, the more complex its pattern of interconnections, the more resilient it will be.

In ecosystems, the complexity of the network is a consequence of its biodiversity, and thus a diverse cological community is a resilient community. In human communities, ethnic and cultural diversity may play the same role. Diversity means many different relationships, many different approaches to the same problem. A diverse community is a resilient community, capable of adapting to changing situations.

However, diversity is a strategic advantage only if there is a truly vibrant community, sustained by a web of relationships. If the community is fragmented into isolated groups and individuals, diversity can easily become a source of prejudice and friction. But if the community is aware of the interdependence of all its members, diversity will enrich all the relationships and thus enrich the community as a whole, as well as each individual member. In such a community information and ideas flow freely through the entire network, and the diversity of interpretations and learning styles - even the diversity of mistakes - will enrich the entire community.

These, then, are some of the basic principles of ecology - interdepen-dence, recycling, partnership, flexibility, diversity, and, as a consequence of all those, sustainability. As our century comes to a close and we go towards the beginning of a new millennium, the survival of humanity will depend on our ecological literacy, on our ability to understand these principles of ecology and live accordingly.”

Thursday, February 20, 2025

A path forward for living laboratories

The following ideas are drawn from my rough draft notes for a research white paper I’m writing at the moment based on my articles since 2007. The paper is intended to be a survey and my reflections of some of the emerging ideas and ages old wisdom born from our community of practice over the last 35-50 or so years, and how we can improve the creations and contributions many of us are making to serving and evolution of capital markets, economic development, business systems, ecological management, regenerative agriculture, circular economy, impact investing, restoration and reconciliation, etc. and all the various approaches you can imagine to find better ways forward:

There is an imperative for a new paradigm that goes beyond sustainable development, one that involves a collective vision for redesigning our civilization, drawing inspiration from nature through biomimicry. At the heart of this transformation is working within planetary boundaries and embracing a city-to-city, citizen-to-citizen cooperative community of practice within a larger bioregional framework. This framework accounts for local community efforts and nature's context within each bioregion from which cities operate.

For example, Mediterranean cities—or leaders within cities residing in Mediterranean climates in one of the four bioregions of that template—can cooperate with each other since they face very similar conditions of climate and the challenges of those unique environments.

To fulfill the grand aspirations of regenerative development and economic transformation, it is essential to establish guiding principles for future inquiry and create contexts that are resilient and adaptable. Adopting a localized approach to development and financing allows for improved coordination and tailors solutions to the needs of specific communities.

There needs to be a new era of cooperation emerging, benefited from the technosphere—the conscious cultivation of communities across the planet harnessing relational bonds that can now be formed through ubiquitous tools like communication networks, videoconferencing, peer learning platforms, cooperative tools, and AI.

Yet to underwrite evolutionary cooperation—a hallmark of the emerging Symbiocene—we need resources. Among these are the eight types of capital, of which money is only one.

We must transcend the logic of the global casino toward a culture of care—place by place, culture by culture, people to people. This new ethos provides a responsibility to steward the collective through this conceptual emergency. Like sailors navigating treacherous narrows, we require deft leaders—systems leaders—who operate with full responsibility to care equally for future and current generations.

This must be grounded in ecological principles, evolutionary systems thinking, and multidisciplinary approaches to resilience. Cooperation has brought humanity this far; we must partner together in new and innovative ways for a win-win society. Emerging scholarship on Darwin’s thinking reveals that cooperative systems increase survival as organisms learned over eons that working together gets us farther than working apart.

From intergenerational wisdom such as the Golden Rule, we must also listen to life's principles through biomimicry and symbiosis—patterns tested over nearly four billion years on Earth—to guide civilization design. For example, we can create curricula inspired by living systems for human settlements, land use planning, and urban-rural landscape regeneration.

By integrating scenarios for opportunities emerging from today’s chaos, we harness collective intelligence to co-creatively architect better futures. This involves creating bioregional regeneration communities of practice—peer-to-peer learning laboratories designed to improve life for families today while ensuring better outcomes for future generations in hometowns, cities, states, and countries worldwide.

We must design ways to steward our heritage and wealth as fiduciaries for our collective inheritance. This requires fully recognizing the incalculable value of Earth's life-support systems that have enabled humanity’s existence.

By reevaluating notions of value, risk, and growth, we can develop a new Modern Portfolio Theory encompassing all treasures—whether tied to places like cities or bioregions or families or neighborhoods. Our worldview must evolve beyond calcified 20th-century models into frameworks suited for 21st-century challenges.

If money makes the world go round, we must redesign how it is managed to unlock wealth embedded in living systems around us. Just as a caterpillar uses its gifts to become a butterfly, we must integrate impact investing with economic development through regeneration—not mere sustainability.

This perspective nurtures ecosystems and communities while fostering innovation through living laboratories that test frameworks for development. Fiduciary responsibility should extend beyond financial capital to encompass all eight types of capital—reflecting holistic views on wealth.

Rather than hoarding insights privately, these tools should serve as public utilities empowering sovereign communities toward stewardship over their collective inheritance.

The fusion between cooperative mindsets across disciplines is essential for integrating impact investing with bioregional development rooted in living systems principles. Observing how plants or animals harmonize with nature offers profound lessons for designing finance aligned with ecological resilience.

Such systems embrace complexity while fostering connectivity, diversity promotion, resilience cultivation—all grounded locally yet regenerative globally—and community-led approaches holistically integrated into finance models ensuring thriving futures.

Were finance allowed evolution serving humanity's needs alongside ecosystems under "Five R’s" (Relationship/Resilience/Regeneration/Reconciliation/Reverence), it would awaken humanity’s sense belonging within interconnected webs spanning life itself.

Bioregional financial systems being developed globally promise flourishing cooperative economies supporting humans alongside ecosystems alike—a transformation requiring expanded imaginal capacities distributing solutions innovatively across cities/bioregions alike accelerating adoption best practices enhancing quality-of-life everywhere.

Monday, February 03, 2025

Expanding Our Perceptual Range: A Systems View of Life, Economy, and Consciousness

Thank you AI:

“ Expanding Our Perceptual Range: A Systems View of Life, Economy, and Consciousness

In the face of mounting global challenges, from climate change to social inequality, it is becoming increasingly clear that our current economic and social paradigms are inadequate. To address these issues, we must fundamentally transform our understanding of life, economy, and consciousness itself. Drawing on decades of research and insight from systems thinking, ecology, physics, and economics, we propose a new framework for perceiving and interacting with our world.

The Limits of Our Current Perception

Our civilization has long operated under a mechanistic worldview, seeing the universe as a collection of separate parts rather than an interconnected whole. This perspective, rooted in Cartesian dualism and Newtonian physics, has led to reductionist approaches in science, economics, and governance. As Fritjof Capra notes, “The major problems of our time cannot be understood in isolation. They are systemic problems, which means that they are interconnected and interdependent.”

Hazel Henderson aptly observes that “the humanoid is a perceiving/differentiating device of limited range inevitably distorts the visioning of the totality.” This limitation in our perceptual apparatus has profound implications for how we understand and interact with the world around us. Our tendency to categorize, separate, and reduce complex phenomena into simpler components has allowed for significant technological progress, but it has also blinded us to the intricate web of relationships that sustain life on Earth.

The Systems View of Life

To transcend these limitations, we must adopt what Capra and Luisi call “the systems view of life.” This perspective recognizes that living systems are inherently interconnected, self-organizing, and emergent. As Buckminster Fuller reminds us, “Synergy is the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system’s separate parts.”

This systems view extends beyond biology to encompass social, economic, and ecological realms. It reveals that the challenges we face are not isolated problems but symptoms of a larger crisis in perception and values. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and economic inequality are all interconnected manifestations of our failure to recognize the fundamental interdependence of all life.

Rethinking Economics and Wealth

Our current economic models, fixated on quantitative growth and monetary metrics like GDP, fail to capture the true wealth and well-being of societies. As Gregory Wendt points out, “We need to recognize these blind spots in our current way of doing business. Once we do so, we can reshape the current model by incorporating these values and ways of seeing the world.”

Hazel Henderson’s work on redefining progress and wealth has been instrumental in this regard. She argues for a more comprehensive understanding of economics that includes the “love economy” of unpaid work, the value of natural capital, and the importance of social and ecological well-being. This expanded view of wealth aligns with Riane Eisler’s concept of a “caring economy” that values nurturing, empathy, and collaboration.

Qualitative Growth and the New Prosperity

Capra and Henderson’s concept of “qualitative growth” offers a crucial reframing of economic development. Unlike unlimited quantitative growth, which is unsustainable on a finite planet, qualitative growth focuses on development that enhances the quality of life without necessarily increasing material consumption. This aligns with what Tim Jackson calls “prosperity without growth” – a vision of human flourishing that doesn’t rely on ever-increasing GDP.

As Buckminster Fuller presciently stated, “We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims.” This requires us to design economic systems that mimic the cyclical, regenerative processes of nature. Concepts like the circular economy and regenerative agriculture are steps in this direction, but they must be part of a broader shift in how we conceive of progress and development.

Expanding Consciousness and Perception

To implement these new models, we must expand our individual and collective consciousness. This involves not just intellectual understanding but a profound shift in how we perceive and experience reality. As Henderson suggests, we need to “write the observer back into the equation” – recognizing that our consciousness shapes the world we perceive and interact with.

Fuller’s concept of “Spaceship Earth” provides a powerful metaphor for this expanded awareness. By seeing our planet as an integrated, finite system of which we are all crew members, we can begin to grasp the true nature of our interdependence and shared responsibility.

This expansion of consciousness has practical implications for decision-making in business, government, and civil society. It calls for what Capra terms “ecoliteracy” – a deep understanding of the principles of ecology and systems thinking applied to social organization.

Technology and Collective Intelligence

Emerging technologies, particularly in the realms of artificial intelligence and global communication networks, offer unprecedented tools for expanding our perceptual range. As Wendt suggests, we must ask, “How does the tool of AI harness the collective wisdom of our human, the noosphere, to create futures which enable our planetary species to evolve far beyond the implicit cognitive limitations of our human conditioning?”

These technologies, when aligned with systems thinking and ecological awareness, can help us visualize and manage complex global systems in real-time. They can facilitate new forms of participatory democracy, collaborative problem-solving, and collective intelligence that transcend traditional boundaries of nation-states and disciplines.

A New Story for Humanity

Ultimately, what we are proposing is a new story for humanity – one that recognizes our fundamental interconnectedness with all of life and our potential for conscious evolution. As Thomas Berry put it, we need a new “story of the universe” that provides a meaningful context for our existence and guides our actions toward a sustainable and flourishing future.

This new narrative must integrate the insights of modern science with the wisdom of indigenous cultures and spiritual traditions. It must bridge the artificial divide between the material and the spiritual, recognizing, as Fuller did, that “Unity is plural and, at minimum, is two.”

Conclusion: Toward a Planetary Civilization

The transformation we are calling for is nothing less than the birth of a new planetary civilization – one that operates in harmony with Earth’s ecosystems and realizes the full potential of human consciousness. This vision, while ambitious, is not utopian. It is grounded in our growing scientific understanding of living systems and the creative potential of human collaboration.

As we face the converging crises of the 21st century, we have the opportunity to make a evolutionary leap in our collective development. By expanding our perceptual range, rethinking our economic systems, and cultivating a deeper awareness of our interdependence, we can co-create a future of shared prosperity and ecological harmony.

The path forward requires us to embrace complexity, cultivate empathy, and develop new forms of governance and economic organization that reflect the true nature of living systems. It calls for a revolution in consciousness as profound as any scientific or technological revolution in human history.

In the words of Buckminster Fuller, “We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims.” The choice is ours, and the time for action is now. By expanding our perception and reimagining our relationship with each other and the living Earth, we can navigate the challenges ahead and realize our potential as conscious agents of evolution.”

Systems View of Life Book Article

Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi explain how their new book captures a different understanding of how life works. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision by Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi is published by Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN: 9781107011366.

The great challenge of our time is to build and nurture sustainable communities, designed in such a way that their ways of life, businesses, economy, physical structures, and technologies respect, honour, and cooperate with Nature’s inherent ability to sustain life. The first step in this endeavour, naturally, must be to understand how Nature sustains life. It turns out that this involves a whole new conception of life. Indeed, such a new conception has emerged over the last 30 years.

In our new book, The Systems View of Life, we integrate the ideas, models, and theories underlying this new understanding of life into a single coherent framework. We call it “the systems view of life” because it involves a new kind of thinking – thinking in terms of relationships, patterns, and context – which is known as “systems thinking”, or “systemic thinking”. We offer a multidisciplinary textbook that integrates four dimensions of life: the biological, cognitive, social, and ecological dimensions; and we discuss the philosophical, social, and political implications of this unifying vision.

Taking a broad sweep through history and across scientific disciplines, beginning with the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution, we chronicle the evolution of Cartesian mechanism from the 17th to the 20th centuries, the rise of systems thinking in the 1930s and 1940s, the revolutionary paradigm shift in 20th-century physics, and the development of complexity theory (technically known as nonlinear dynamics), which raised systems thinking to an entirely new level.

During the past 30 years, the strong interest in complex, nonlinear phenomena has generated a whole series of new and powerful theories that have dramatically increased our understanding of many key characteristics of life. Our synthesis of these theories, which takes up the central part of our book, is what we refer to as the systems view of life. In this article, we can present only a few highlights.

One of the most important insights of the systemic understanding of life is the recognition that networks are the basic pattern of organisation of all living systems. Wherever we see life, we see networks. Indeed, at the very heart of the change of paradigms from the mechanistic to the systemic view of life we find a fundamental change of metaphors: from seeing the world as a machine to understanding it as a network.

Closer examination of these living networks has shown that their key characteristic is that they are self-generating. Technically, this is known as the theory of autopoiesis, developed in the 1970s and 1980s by Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela. Autopoiesis means “self-making”. Living networks continually create, or recreate themselves by transforming or replacing their components. In this way they undergo continual structural changes while preserving their web-like patterns of organisation. This coexistence of stability and change is indeed one of the key characteristics of life.

In our synthesis, we extend the conception of living networks from biological to social networks, which are networks of communications; and we discuss the implications of the paradigm shift from the machine to the network for two specific fields: management and health care.

One of the most rewarding features of the systems view of life is the new understanding of evolution it implies. Rather than seeing evolution as the result of only random mutations and natural selection, we are beginning to recognise the creative unfolding of life in forms of ever-increasing diversity and complexity as an inherent characteristic of all living systems. We are also realising that the roots of biological life reach deep into the non-living world, into the physics and chemistry of membrane-bounded bubbles — proto cells that were involved in a process of “prebiotic” evolution until the first living cells emerged from them.

One of the most important philosophical implications of the new systemic understanding of life is a novel conception of mind and consciousness, which finally overcomes the Cartesian division between mind and matter. Following Descartes, scientists and philosophers for more than 300 years continued to think of the mind as an intangible entity (res cogitans) and were unable to imagine how this “thinking thing” is related to the body. The decisive advance of the systems view of life has been to abandon the Cartesian view of mind as a thing, and to realise that mind and consciousness are not things but processes.

This novel concept of mind is known today as the Santiago theory of cognition, also developed by Maturana and Varela at the University of Chile in Santiago. The central insight of the Santiago theory is the identification of cognition, the process of knowing, with the process of life. Cognition is the activity involved in the self-generation and self-perpetuation of living networks. Thus life and cognition are inseparably connected. Cognition is immanent in matter at all levels of life.

The Santiago theory of cognition is the first scientific theory that overcomes the Cartesian division of mind and matter. Mind and matter no longer appear to belong to two separate categories, but can be seen as representing two complementary aspects of the phenomenon of life: process and structure. At all levels of life, mind and matter, process and structure, are inseparably connected.

Cognition, as understood in the Santiago theory, is associated with all levels of life and is thus a much broader phenomenon than consciousness. Consciousness – that is, conscious, lived experience – is a special kind of cognitive process that unfolds at certain levels of cognitive complexity that require a brain and a higher nervous system. The central characteristic of this special cognitive process is self-awareness. In our book, we review several recent systemic theories of consciousness in some detail.

Our discussion also includes the spiritual dimension of consciousness. We find that the essence of spiritual experience is fully consistent with the systems view of life. When we look at the world around us, whether within the context of science or of spiritual practice, we find that we are not thrown into chaos and randomness but are part of a great order, a grand symphony of life. We share not only life’s molecules, but also its basic principles of organisation with the rest of the living world. Indeed, we belong to the universe, and this experience of belonging makes our lives profoundly meaningful.

In the last part of our book, titled Sustaining the Web of Life, we discuss the critical importance of the systems view of life for dealing with the problems of our multi-faceted global crisis. It is now becoming more and more evident that the major problems of our time – energy, environment, climate change, poverty – cannot be understood in isolation. They are systemic problems, which means that they are all interconnected and interdependent, and require corresponding systemic solutions.

We review a variety of already existing solutions, based on systems thinking and the principles of ecodesign. These solutions would solve not only the urgent problem of climate change, but also many of our other global problems – degradation of the environment, food insecurity, poverty, unemployment, and others. Together, these solutions present compelling evidence that the systemic understanding of life has already given us the knowledge and the technologies to build a sustainable future.

Fritjof Capra, physicist and systems theorist, has been engaged in a systematic examination of the philosophical and social implications of contemporary science for the past 35 years. Pier Luigi Luisi is Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Rome. His main research focuses on the experimental, theoretical, and philosophical aspects of the origins of life

Saturday, October 05, 2024

Synergetics opening

Tuesday, August 15, 2023

Friday, July 28, 2023

Friday, September 30, 2022

Sunday, August 14, 2022

We are The Movement Of Coherence

“A specific type of leadership is required that would have the authority and resources to convene and maintain the dialogues for developing shared visions and perspectives. A GCM might develop a new form of leadership—movement diplomats—that would complement civil society’s paid staff, charismatic visionaries, influential philanthropists, community organizers, and organizational heads. Trained and supported directly by organizations or communities, these diplomats would be charged with the task of building systemic coalitions. They would seek to translate the rhetoric of different factions, foster communication, and find common ground. They would provoke learning in their own organizations in addition to reaching out to form alliances. Ideally, this new evolution in leadership would include core competencies of facilitation, strategic dialogue, systems thinking, and familiarity with future scenarios and the requirements for a sustainable world. This new role of leadership would not replace other necessary types of leadership, but would complement them in helping to maintain the balance between coherence and diversity within a GCM.”

“This difficult work of diplomacy, often unglamorous and contentious, could become a highly respected and influential form of leadership. If such roles are given recognition and support, a network of movement diplomats and diplomatic training programs could help a systemic movement overcome barriers of language, class, region, and outdated “issue-silos”. It would be through the work of these diplomats that spaces for engaged dialogue would be developed, multiplied, and enhanced. Movement diplomats could be a key to developing coherence while avoiding the evolution of stultifying movement hierarchies.”

From “Dawn of the Cosmopolitan The Hope of a Global Citizens Movement”

Orion Kriegman

Sunday, August 01, 2021

Why do we pursue improving impact investing?

Wednesday, May 26, 2021

informing the blind spots in our economic models - through thinking about new ways to perceive and differentiate.

"The ferment Heisenberg caused in physics is now leading to efforts by Wheeler, Everett, Capra and Wigner and a host of audacious young physicists to write the observer back into the equation - an overdue recognition of the most basic of the "hard" sciences that, in a very real sense, reality is what we pay attention to. In fact, the humanoid is a perceiving/differentiating device of limited range inevitably distorts the visioning of the totality. Indeed perhaps original sin is nothing more than differentiating, out of which grows such communal grief. Out of more holistic insights we may discover a different view of probability theory, rooted in the understanding that “randomness” and “disorder” are only measures of human ignorance. While of peripheral vision, by the drive of “probabilities,” was an imaginative leap, perhaps we may also embrace the possibility that those “probabilities” actually exist, even though we are not paying attention to them, as the many worlds-interpretation in quantum physics suggests.” ~ Hazel Henderson from her book 1976 book "Creating Alternative Futures, the End of Economics"

Saturday, January 30, 2021

Toward a new model framework for finance to build a common good capitalism

Sunday, January 17, 2021

first draft: From Charting A New Course For Impact Investing, To Sailing to New Seas Only Imagined

[this is a rough draft, please pardon the typos]

MONEY MEANING AND MARKETS

Now that nearly 18 moons has passed since Ethical Markets published

this piece, which I co-wrote with Nick Sramek, based on our share visions and experiences, his as a knowledge officer at a thin tank guiding pensions and family offices and mine a nearly three decade passion for sustainable development, green economy and ethical investing.

After the article has opened up so many doors for us, and strengthened the convictions I had about the nature of evolving finance, and while Nick and I had complementary visions, my experience in creating this piece is as if it could been either of ours, and both of ours at the same time. And neither of us really thought we invented any ideas in the article, yet we were simply looking to assess the state of affairs of a movement over the last decade in anticipation of the 10th anniversary of the conference, as a human created demarcation point to pause, and reflect "what will the next decade be like?" We felt that to articulate and corroborate a shared understanding of the thought leadership in the field, we could increase the diffusions of innovation of thought theory and practice more rapidly, thus bringing about the desired futures more readily and rapidly.

The article somewhat draws from the number of years I wrote about my experiences at the Social Capital Markets Conferences (SOCAP) and the people who inspired the movement, and me, the most. The conference is the opening of the article, and the setting is where the conference is held, in golden October sunshine overseeing sailboats and steamships on San Francisco Bay at Fort Mason with an ever present view of the incredible international orange paint on golden gate bridge and the vast redwoods on the other side.

There’s an essential arc in the article, a through line, which is drawn like a golden thread through some of the minds who architected the foundational layers of the new economy and responsible investing movement in the 60's, 70's and '80's and some of the earliest social entrepreneurs and innovators in finance which led to the current forms of ESG and Impact Investing. Yet, as systems grow and evolve, so do it's ideas, and as ideas evolve, so do systems. We cannot create something we cannot imagine. Nor can we see the butterfly in the caterpillar, yet it is encoded within. Similarly each of the people mentioned in the bullet points are calling for something more comprehensive, sensitive, complex, nuanced, contextual, effective or systemic. All based on new ideas and paradigms. In many ways these ideas are the foundational architecture of the new economy movement. There are a range of shifts going on the spectrum of systems, such as:

- From Impact Investing to Integrated Finance “The Clean Money Revolution” – Joel Solomon

- From Sustainability to Regenerative Economics “A Finer Future”- Hunter Lovins, John Fullerton et al

- From Economism to Earth Systems Science – Mapping the Transition to the Solar Age Hazel Henderson 2014

- From Reductionist Thinking to Systems Thinking Biomimicry for Finance 2012 Statement for Transforming Finance based on Ethics and Life’s Principles Hazel Henderson, Jeanine Benyus and others at Ethical Biomimicry Finance

- From Financial Capitalism to Mutual Impact and Deep Economy Jed Emerson – The Purpose of Capital

- From Ego-System to Ecosystem Economies Otto Sharmer Leading from the Emerging Future

- From Extractive Businesses to Regenerative Business Carol Sanford Regenerative Business

- From Conventional Capitalism to Common Good Capitalism Terry Mollner, Common Good Capitalism

- From Billions To Trillions In March 2018 the concept paper From Billions to Trillions: How a transformative approach to collaboration and finance supports citizens, governments, corporations, and civil society to share the burdens and the benefits of solving wicked problems

- From Private Banks to Public Banking Public Banking Institute

- From the New Deal to the New Grand Strategy and the New Green Deal “New Grand Strategy” Patrick Doherty, Puck Mykelby and Joel Makower

The essential pull in this article is north star of multigenerational human prosperity through rethinking the pathways and means to evolve markets and money systems. Each of these thinkers and social entrepreneurs sought to meet the growing volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity in our civilization with more comprehensive systems approach, often born out of the context of their personal experiences. Each of them point toward an increasingly complex form of managing our economy and the store and exchange of value. And essentially we're going through a phase shift from one form of civilization to another. Some are calling this the new axial age.

Not unlike the Copernican Age from waking up to the fact that we orbit a star, or the rennaissance, yet this one feels like a shift toward something deeper, toward the collective interior of thought, and ideation. We are challenged to the core in our belief systems, perhaps because it's not about beliefs, but about meeting the world for what it is now, as what we believe is from what was, not is.

So if our institutions were based on the information processing limits of the technology of their times, then let's evolve the culture of decisionmaking with a broadening of stakeholders, and the contextual data for each and every dimension of our community of life. We can then shift, from reductionist monetary systems based on a rare commodity such as gold, or shells, often associated with self limiting ego oriented cultures, silo thinking and institutional regimens based on earlier modes of civilization toward a more comprehensive systems approach for managing the affairs of our communities and bioregions. From walls to ways to relate.

The notion of evolving economic development, or the practice of evaluating myriad economic development paradigms is an important one for us to have better results from our business clusters and governance systems. We will be able to enhance the value drawn from innovative entreprenuership and business clusters. When we see a larger context from our enterprises, and adding additional bonus points of environmental, social and cultural regeneration, we have a longer view to work from. To the lives of our kids, and their grandkids. And theirs. We can then have a clearer sense of the path ahead, and where the path we are walking are walked by others, on the same ground in a different time.

We can then be focused on the full spectrum of what is going on around us in our places now, incorporating Environment Social and Governance Factors into our planning and decisionmaking for harmony and mutual prosperity for each other and our planet. The various regions on our planet, which have a range of climate, plant and animal patterns - or classification of types of bioregions in frames such as rainforest to desert to coastal tundra, or mediteranean to nordic or tropical to alpine. With these patterns of climate and resource contexts - we see emerging patterns and challenges. For example cities in desert regions have different infrastructure challenges than cities in subtropical cities adjacent to rainforests. Thus the solutions and projects will evolve in bioregional patterns, and also you can see the pattern of agriculture has patterns that map across the globe depending on climate.

We saw this context of place based, full spectrum accounting vision for human activity as a north star, inspired in part based on the patterns and strategies of life over the last 4.3 billion years. I led a series of conversations and panel discussions at the SOCAP Conference in 2014, 2015 and 2016 under the banner of "biomimicry for finance" and the last panel had a bioregional twist. We titled the event "Building an Economic Ecosystem Like 3D Chess - Local, Regional and Systemic" and that is where we began seeing bioregional thinking really enter our thinking, based on the many years of work of scientists in the field.

More recently, OneEarth has created a bioregional map for planet earth. Imagine this as a pattern to organize our cities and their related supply chains. Wouldn't it help us shapeshift agriculture, infrastructure, economic decisionmaking, and long term urban planning with a new set of ingredients?

Were we to allow finance to simply evolve to serve the 21st century needs for what I feel are the 5 R's relationship, resilience, regeneration, reconciliation, and reverence, in partnership with the community of all life. This would turn finance into a better tool in service to our humanity, to meet the needs of current and future generations at the same time, by simply waking up out of our dream of separation from life into seeing our belonging, each of us in community with the whole of humanity and our massive inheritance of the bounty of earth

“Charting a New Course For Impact Investing”

We feel it is essential that we imagine better ways to approach questions such as:

- How economic development be evolved by adopting systems approaches? And shifting economic behavior to the limits of the biosphere in each bioregion, and optimizations for innovation and efficiency of energy use (along the lines that a more efficient form of life often has more longevity)

- How can impact investing (also known as Socially Responsible Investing, ESG, Ethical Investing, triple bottom line, SDG’s etc.) evolve to shift the underlying economic paradigm in a community of practice, or industry? How can we collecitvely incorporate living systems to improve our business models and theories of change?

- How can we build on the successes of leaders for decades, and help bring our collective visions into form - there are a number of areas where our model of operation is evolving "from -> to” and in some ways the cognitive leaps feel logarithmically more complex than the previous stage. Please see items below.

- How can we all come to a better shared understanding the aforementioned themes of economy, longevity and progress in far simpler terms? We know our place, we want to live in tune with the gifts in life. We all want to and to be feel more love and connection, connected to our beloved families and friends, have lives full of prosperity pleasure and meaning filled lives. We can all identify with these fundamental human values - and also to have clean air, healthy tasty food, and enjoying the ups and downs in life in the company of those who we love the most. These are among fundamental human traits, and as we are part of the web of life, then it's clear that somehow we are all part of each other’s living experience in some way, or at least you are connected to anyone who has read this far in the article.

By way of background, I have a wide range of activities with a focus on evolving capital markets and impact investing systems:

-

I launched and led the the CA Capital Markets Task Force ( see bottom of page 15 ) with local,

regional and statewide leaders to evolve the application of impact

investing at the country level scale in the 5th largest economy on the

planet, the article is the guiding philsophical framework of the Task Force.

- I also have a small private practice for comprehensive wealth management ESG/Impact

- We are scoping a range projects in development with ESG industry pioneers to bring our greatest ideas for scaling impact investing into communities from regenerative systems and public banking to urban resilience and blockchain capital market innovation.

Please reach out anytime so we can discover what's possible together! Find me on linked in

Here's the original article, as published on July 4, 2019

Charting a New Course for Impact Investing: The Emerging New Paradigm of Living Systems for Capital Markets

“Ethical Markets highly recommends this reframing of the global issues surrounding mainstream finance and its inability to move beyond its anthropocentric, theoretical models derived from obsolete textbooks, now encoded in ETFs, the millions of indices, benchmarks, algorithms and theme-based portfolios.

We refer to these kinds of “theory-induced blindness,” identified as cognitive biases by psychologist Daniel Kahneman in “Thinking Fast and Slow ( 2011)” and in our latest Green Transition Scoreboard ®: “TRANSITIONING TO SCIENCE-BASED INVESTING: 2019-2020” (downloadable at www.ethicalmarkets.com) as unrecognized financial risks: “science-denial.” (beyond the climate-denial exhibited in stranded fossil reserves still in too many portfolios).

The anthropocentrism in the conceptual framing still taught in business schools and used in the global mainstream financial system blinds asset managers to the real world science of planetary processes reported in real time by the 120 Earth-observing satellites of NASA, ESA and other nations’ space programs, which we cover on our Earth Systems Science page.

We hope this thoughtful re-appraisal by two expert financiers, will help sharpen this needed debate we cover in our global TV series “Transforming Finance” distributed by www.films.com. Comments welcome.

~Hazel Henderson, Editor”

Charting a New Course for Impact Investing:

The Emerging New Paradigm of Living Systems for Capital Markets

Nick Sramek & Greg Wendt

July 1, 2019

Summary:

Despite efforts to bring the two closer, impact investing and traditional finance suffer from a misalignment challenge. Since the goals of traditional finance are inherently separate from the qualitative dimensions of values-based investing, creating mechanisms to bridge the gap has been ineffective up to this point. A new framework is needed – and is currently being constructed. All investors must coalesce around principles that have been with us for millennia; the same principles that dictate a natural order have the power to build long-term profitable companies, positive economic returns for investors, resilient communities, and sustainable ecosystems.

Expanding the role of finance is necessary to build long-term resilience which must start with multi-layered systems thinking. Listening to the needs of communities, cities, companies, investors and bioregions – the building blocks of a sustainable society – as a tree listens to its roots – will allow for far greater alignment between companies, investors, communities and the environment. For all of these building blocks, creating systems that have a 100-year vision must be the goal (to create the necessary preconditions for the intergenerational transfer of true prosperity). Taking a long view of how we live today and want to live in 100 years – and perhaps 10,000 years – has the power to not only stave off negative externalities but also repurpose our current systems for a greater good.

I. Remembering the Past

“The whole wilderness in unity and interrelation is alive and familiar … the very stones seem talkative, sympathetic, brotherly … No particle is ever wasted or worn out but eternally flowing from use to use.” – John Muir

Imagine yourself strolling below the towering redwoods of Muir Woods in Northern California, needles crunching below your feet, just as John Muir and his friends must have felt when they walked the same path. Can you hear the stones, and perhaps trees talking together? Can you? Even if trees could think, would we be able to listen to their thoughts? Could we imagine what those trees feel, strolling underneath their canopy?

Perhaps Muir has asked himself: are we thinking for the rocks and trees or with them?

In simple moments of reflection on the big picture, we can see that we are part of a living system, what visionary biologists call Gaia. And even reductionists would admit Earth is a system of living systems, an ecology of ecologies.

In order to connect ecology to economic development, in 1988 the UN coined the phrase sustainable development and asked how do we create “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” ?

Or perhaps a more relevant question is:

How do we harmonize the systems of economic development, wealth creation, and finance into greater coherence, to align with living systems upon which our very civilisation is built to actually improve them for future generations?

The good news is that attention is increasingly focused on the challenges of today and tying in the ecology of ecologies of our own systems. Leading groups across the planet have charted a course for this new economic framework based on a whole systems approach. And even established firms such as Goldman Sachs, Bloomberg, Nuveen and Blackrock who in the past resisted weaving environmental and social values with markets, are moving in this direction, perhaps simply motivated to serve the growing demands from customers who want their money managed in alignment with their values (yet movement is being made nonetheless). Many leading impact investing and ESG organizations are touting deepening strategies within values-based investing, promising that billions of dollars of capital will funnel into sustainable investment. They claim to have a real impact on people and the environment; from most accounts, a monumental shift is upon us.

However – is this really the case? Can this growth really be attributed to a growth in investor sentiment? Or merely a growth in opportunities that provide market rate returns? In other words – is the financial community truly creating strategies for long term sustainability, or simply reacting to short term trends for money-making opportunities? I.e. is the growing investment in renewable energy simply due to economic viability or does this represent true growing environmental awareness in the investor community? Which axis is moving? Greater openness to values-based investing – or the emergence of market returns for areas that were previously not economically viable?

One of the challenges we observe is that traditional financial markets operate as if the players are children vying for the attention of their parents rather than for the benefit of the whole family. The dynamics in the wall street model with stakeholders working in competition is antithetical to the necessity of cooperation to build the field and move the whole marketplace to an entirely different paradigm.

This is already happening in many circles such as SOCAP, CERES, GIIRS, B-LAB, TBLI, GIIN etc. yet many actors in the “impact investing space” are playing with the old wall street rules, which do not encourage cooperative behavior and implicitly require zero sum competition. Yet we are no longer competing children building sandcastles on the beach, expressing the virtues of our castle over all others. We must be aware that the very act of creating the castle inspires others to create even better castles, and the impressions we leave on others is the act of creation, letting the castle itself dissolve into the sea. The irony here is that impact investing aspires to be much more inclusive, cooperative and holistic in it’s approach, yet often vies to compete directly with traditional financial markets.

Fortunately, we see a new pattern emerging, a new way of relating, and building the outcomes desired by impact investors. This new pattern shows much promise to improve every community across the planet.

II. Breaking Through: Building New Models for Investors

What you’re supposed to do

when you don’t like a thing is change it.

If you can’t change it,

change the way you think about it.”

-Maya Angelou

What does it take to reinvent finance to achieve the desired outcomes for our planet while building resilient communities and strong economies?

Investing traditionally lives in a two-dimensional spectrum. On one end of this line lies pure capitalism – one hundred percent transactional in nature and uncompromising in it’s goal of profit. On this end, everything goes. Environmental degradation for a quick buck? No problem. Exploitation of underprivileged groups to increase productivity? Why not. At the other end of the spectrum lies pure giving – where economic goals do not matter at all, and every dollar spent towards non-economic returns – such as environmental sustainability and human rights – completely justify the means. No financial return here is necessary or expected. Every other transaction can then be attributed to some point on this continuum.

This continuum has been the focus of modern finance in recent decades as investors choose their position along this line. Chief Investment Officers interpret, re-interpret and occasionally reframe their investment thesis to justify ways their strategy serves the evolving priorities of their stakeholders in light of fiduciary responsibilities. Sometimes, positions change – many point to the glacial evolution of impact investing down the river as a sign of the next great wave of investment into social and environmental causes. Due to announcements such as the 2018 US SIF report, many conclude a sea change is right around the corner.

But what if that sea change is not right around the corner? What if a new paradigm is necessary to achieve these goals?

Finding True North

What if instead the final goal is not sacrificing economic returns for environmental/societal benefits, but leaving the era of transactional finance vs philanthropy and arriving at an era of longevity?

In this space, there isn’t an argument as to which side is right or where we need to land along the continuum. We simply need to ask better questions together. How do we support the betterment of all of our stakeholders, both tangible and intangible? How do we ensure our company will be around in 100 years? Do we want customers to be proud of what our company has embraced toward a shared long-term vision? .

In this space, there is room not only for short-term profit (which will exist, it’s important to note), but also greater coordination – economic, environmental, social – between the needs of communities and the needs of investors. This is not economic development – that misses the point of fully leveraging the financial wealth that has the power to save the world. Financial reform also misses the point – as financial reform without a new sense of a shared long-term goal will only amount to a burdensome regulatory regime that will be actively thwarted by those seeking to return to the status quo. Equally important to creating a shared vision is to honor what each force brings to the table. As we disassemble the spectrum, pieces cannot be discarded, but repurposed in a way that actualizes their best characteristics while heightening the overall impact. Since impact investors have already taken the leap toward weaving all of these factors into investing process, an entirely different mindset and whole systems paradigm is needed.

In order to best utilize these pieces, greater coordination is absolutely necessary between traditional players and the impact investing community to find common ground in every economic development context. A new lode-star must be calibrated to zero degrees, where the long term aims of financial institutions, impact investors, retirement portfolios, sovereign wealth funds, and development dollars are aligned. Perfect alignment should be the goal; but for the time being, the financial sector needs to at the very least be able to sit down and dream about what they want their considerable assets to accomplish. As an example, the growing number of actors working to create development initiatives, funds and investment pathways for opportunity zones are growing faster than ever, yet many in the space are presuming by simply bringing more money to such communities, wealth will spread. Yet very few groups are actually building investments which explicitly measure and incorporate the range of opportunities and factors to meaningfully improve the quality of life in the communities within and surrounding the zones. Applying this larger set of tools and processes to measure all dimensions of wellbeing is needed.

Creating a New, Powerful Framework of Systems

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality.

To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

– Buckminster Fuller

The next step in the development of our financial institutions is absolutely crucial to stave off the dual threats that have the power to forever change communities in virtually every corner of the world – inequality and environmental degradation. Resolving this conundrum is quite literally the trillion dollar question – creating the appropriate structure to move trillions of dollars to developing robust communities and resilient ecosystems has the power to transform our world and build wealth in a new and profound way. Greater coordination is at the center of this challenge – which is far outside the bounds of any written expose. Here, the goal is to not pitch a solution, but simply articulate our current standoff and provide an actionable context to create living laboratories.

This article, first of a series, is not an attempt to answer questions, but to outline the range of questions and allow for community and state leaders, financial institutions, and economic development bodies to lay out guiding principles for future inquiry and to build contexts sufficiently robust to fulfill the promise of impact investing. These principles should include actions that allow for long-term alignment for companies, investors, governments, and communities; allowing for all of these groups to build a common resilient structure based on systems thinking must be the ultimate goal.

While our lives are unquestionably global, we reside in communities. We attend state universities, travel on county roads, use city fire departments, and rely on neighborhood watch groups. As communities are and will continue to be the building blocks of society, it is important to base solutions to challenges on the needs of our neighbors. A localized approach to development and financing will allow for greater coordination – financial institutions can then respond and provide long term solutions for community challenges. It is here, where these institutions can clarify a long term vision of what they want their assets to accomplish and thus create a context to find shared values, common language and context of cooperative behavior, community by community.

These building blocks can then be stacked – from individuals, to, community to city, city to state, and state to nation, allowing for a coordinated capital flow where incentives are tied to creating better, safer and healthier communities. This would of course rely on a massive leap of faith from those who benefit from inequality and extractive industries. A new Modern Portfolio Theory must be constructed for the 21st Century – one that takes into account sustainability, biomimicry, and economic development – in order to coordinate long term incentives. Luckily, since our wealth and power are tools can be used in many different purposes, with the power to build up or tear down; multiply or disappear. It is incumbent on us to build on the success of over 50 years of values driven investing to organize in a new form, like creating 21st century buildings with new mortar and the bricks of the current system’s players. From this simple shift of approach of weaving impact investing with economic development we can transform unlike any economic development agency has the potential to do. Finance transformed can help build a new world – if we allow it to.

No Institution is an Island

Shared prosperity requires the ability to see the forest for the trees – while not losing sight of the path in front of us. The ability to see the forest floor, to listen to the animals at our feet, while also soaring above with a birds-eye view. Unfortunately, while proper coordination is far and few between, it is central to reducing inefficiencies and maximizing the potential of investment dollars, governments and communities. Coordinating public and private institutions at the regional and sub-regional level will allow for a heightened understanding of our unique challenges – and shared goals.

Pockets of community-based thinking are beginning to emerge in regions across the world. One small example is the “pledge LA” program in Los Angeles that seeks to connect venture capitalists across the LA basin with community development organizations, government groups and economic developers in order to accelerate investments into startups and initiatives that will have a positive impact on communities and the environment. Pledge LA seeks to address equity, diversity and inclusion. This type of coordination has the ability to build new conversations among traditional players for the public good, while sharing risk, ideas, and innovations in communities.

In turn, this allows investors to do more with their influence and dollars and provides regional civic leadership and economic development authorities the means to accelerate their own mission for improving the quality of life for all participants in the regional economy. What remains to be addressed is the creation of robust and effective tools and incentive structures to allow for this high level of coordination to take place and demonstrate measurable results for communities from the dollars and influence invested. Here, a consensus needs to be reached on appropriate risk-sharing and profit-sharing mechanisms.

Similarly, in Silicon Valley, a community we have all looked at as a leading example for innovation and wealth creation, Victor Hwang of the Kauffman Foundation once compared the successful tech market of ideas and capital to a rainforest. Yet was he studying the way a forest really works in order to listen and learn from it? Or simply projecting his views into a transactional understanding of what a forest actually is? Does one tree stand triumphant over all the others, or is there some coherent order beneath the soil, which every tree knows, and every critter knows, to create a system designed to be regenerative?

In both examples the question remains; are the traditional tools for investing, economic development, measurement and decision-making on a regional level sufficient to take on the grander aspirations of regenerative development?

III. Joining a Community: The Transition is Happening All Around Us

“They always say time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself.”

– Andy Warhol

Luckily, programs as inspirational as Pledge LA and the Kauffman Foundation’s efforts continue to inspire brilliant people to continue building the components for a new economic reality toward a true triple bottom line economy. All of these building blocks are heading in the same general direction. These communities of practice continue to create novel impact investing frameworks which provide the meaningful preconditions to fulfill the promise of full economic transformation and to create living laboratories to test and apply novel development frameworks.

In recent years, a growing number of thought leaders have been articulating the systemic shift needed for impact investing to truly accomplish its goal of transforming the economy. The vision we are calling for here is well underway.

Each of these perspectives are speaking toward a more comprehensive and inclusive set of activities to build on the success of the past, and weave a more coherent fabric for investors to support advanced economic development for the well being of communities across the world. We’ve compiled a list of recommended pathways to explore this revolutionary change:

- From Impact Investing to Integrated Finance “The Clean Money Revolution” – Joel Solomon

- From Sustainability to Regenerative Economics “A Finer Future”- Hunter Lovins, John Fullerton et al

- From Economism to Earth Systems Science – Mapping the Transition to the Solar Age Hazel Henderson 2014

- From Reductionist Thinking to Systems Thinking Biomimicry for Finance 2012 Statement for Transforming Finance based on Ethics and Life’s Principles Hazel Henderson, Jeanine Benyus and others at Ethical Biomimicry Finance

- From Financial Capitalism to Mutual Impact and Deep Economy Jed Emerson – The Purpose of Capital

- From Ego-System to Ecosystem Economies Otto Sharmer Leading from the Emerging Future

- From Extractive Businesses to Regenerative Business Carol Sanford Regenerative Business

- From Extractive Economics to Inclusive Economic Development Blueprints Restoring Dignity to Economic Development with Individual Collectivism

- From Conventional Capitalism to Common Good Capitalism Terry Mollner, Common Good Capitalism

- From Billions To Trillions In March 2018 the concept paper From Billions to Trillions: How a transformative approach to collaboration and finance supports citizens, governments, corporations, and civil society to share the burdens and the benefits of solving wicked problems

- From Private Banks to Public Banking Public Banking Institute

- From the New Deal to the New Grand Strategy and the New Green Deal “New Grand Strategy” Patrick Doherty, Puck Mykelby and Joel Makower

Now, a coherent throughline is emerging, where all of these voices are speaking to a central theme of a more systemic approach to the key challenges of our time. We aim in future articles to further explore this growing coherence and common themes arising from the community of thought leadership.

IV. Towards Greater Cooperation

“We’re like bees, you see, bees that go out looking for honey without realizing we’re performing cross pollination” – Buckminster Fuller

Yet, we are not bees, we are humans, so it is time to cooperate to create an even better system of cross pollination as it were, in context of every bioregion and evolve the system together as many are calling for.

We must change our approach, as outlined above, and then apply this new vision and methodology in the context of communities and bioregions across planet earth. From this, there is an opportunity to accelerate toward a blue ocean shift that weaves these evolutionary efforts to transform the paradigm which guides us.

Many groups are well under way with exploring and applying the possibilities of these new approaches, such as Impact Assets, RSF Social Finance, Regenerative Communities Network, BluePrints, Ethical Biomimicry Finance, Social Capital Markets, Transform Finance, Transform Community, and many others. Yet the vast majority of investors and economic development professionals in these circles are still encumbered with siloed thinking – by simply focusing on one issue or one dimension of the system. Many have been listening to the call for collective action for some time, yet in order to weave our thinking and evolve traditional approaches to economic development and finance, we must build novel approaches and perspectives outside the box.

It’s encouraging that new pathways are being developed all over the world that aim to expand on the central ideas outlined here today – to revisit our assumptions about capital markets evolution, to increase the efficacy of impact investing, and to build in systems thinking to our long term plans. It’s through the development of this long-term plan that we can first ensure that we create resilience for the next 100 years, repurposing the effective but incongruous models of today for the needs of future generations. Here, we are creating fertile soil for an intergenerational transfer of stewardship to improve our environment, communities and economy, and create the preconditions for a regenerative capital markets framework to fully take root.

“There is not a fragment in all nature, for every relative fragment of one thing is a full harmonious unit in itself.” – John Muir

Now, with our feet firmly planted in the dirt, feeling the roots beneath our feet and under the canopy of leaves over our head, we must walk together on this path towards long-term resilience.

NS & GW

[Obviously, the ideas contained within this article go far beyond its intended scope and should be seen only as a place of departure. If you wish to continue this conversation, and contribute to future articles or join the events we are creating – please reach out to us on LinkedIn Nick Sramek & Gregory Wendt]